This article was originally published on Substack.

Imagine asking a question in plain English like "How has my month-on-month revenue been in this quarter?" and instantly getting a precise answer right from your company's database, supported with a nice visualization, without knowing anything about databases or how to write an SQL query. This is the promise of Text-to-SQL systems, which bridge natural language and relational databases. By translating natural language questions into structured database queries, Text-to-SQL democratizes data access, empowering non-technical users to extract meaningful and deeper insights from complex databases with ease.

While the concept sounds straightforward "Just let the LLM write the SQL" but the reality is far more nuanced. Human language and SQL are fundamentally mismatched.

Text-to-SQL systems are hard to build

SQL is rigid, precise, and unforgiving. Natural language is ambiguous, contextual, and fluid. Bridging this gap requires more than just "translation." It demands a deep understanding of intent, schema, semantics, and the ability to navigate a minefield of technical constraints. Let's break down why this is hard:

Everything should be semantically meaningful for AI to make sense of

When a user asks, "Show me staff in marketing hired after 2020," the LLM must:

- Map "staff" → employee table

- Infer "marketing" → department_name = 'Marketing'

- Translate "hired after 2020" → hire_date > '2020-12-31'

But what if the schema uses dept_id instead of department_name, or the user says "team" instead of "staff"? Misinterpretations here lead to queries that either fail or return garbage.

SQL requires precision

Unlike a chatbot that can approximate an answer, SQL demands absolute correctness. A missing JOIN, an incorrect GROUP BY, or a misplaced HAVING clause doesn't just degrade results; it crashes the query. For example:

User asks: "Total sales per region last year."

The AI must:

- Join sales, regions, and time tables

- Aggregate with SUM() and GROUP BY region

- Filter dates to the previous year, requiring the context of the current date

One missed step, and the answer is wrong.

Messy database schemas

Real-world databases are rarely designed for LLM comprehension. Cryptic column names (e_add for "employee address"), denormalized tables, and legacy design choices turn schema mapping into a puzzle. For instance:

- A user's "project end date" might live in projects.end_date or assignments.termination_date, depending on the schema.

- A query like "Who manages the sales team?" requires knowing that departments.manager_id maps to employees.employee_id, a foreign key relationship invisible in natural language.

Complexity ceiling

Simple queries (e.g., filtering a single table) are manageable. But as questions grow in complexity, like "Show me employees in the sales department who joined after 2020, are working on active projects, and have had a salary increment of over 10%," the LLM must orchestrate:

- Multi-table joins (employee, departments, projects, salaries)

- Subqueries to compare historical salaries

- Date arithmetic and conditional logic

Even humans struggle with such queries, and expecting AI to nail this consistently is a tall order.

UX challenges

When a SQL query fails, users don't get a "close enough" answer they get a database error or empty results. Imagine a non-technical user seeing:

ERROR: syntax error at or near "WHERE"Or worse: a query that runs but returns the wrong data due to a logical flaw (e.g., missing DISTINCT in a count). Unlike creative writing or summarization, there's no room for "hallucination" in SQL.

How Do LLMs Actually Generate SQL Queries?

While Text-to-SQL systems may feel magical, their capabilities are rooted in rigorous training and structured prompting. They are typically trained and fine-tuned on benchmark datasets:

- Spider: The gold standard for complexity, featuring 200+ databases and 10,000+ questions spanning healthcare, education, and more. It tests multi-table joins, nested queries, and advanced SQL logic.

- WikiSQL: A simpler but massive dataset (80,000+ examples) focused on single-table queries ideal for mastering basic SELECT, WHERE, and GROUP BY operations.

- SParC/CoSQL: Built for conversational SQL, these extensions of Spider handle multi-turn interactions (e.g., “Now filter those results to show only managers”).

These datasets teach models to map phrases like "employees" → staff_table and "hired after 2020" → hire_date > '2020-12-31'.

What happens under the hood?

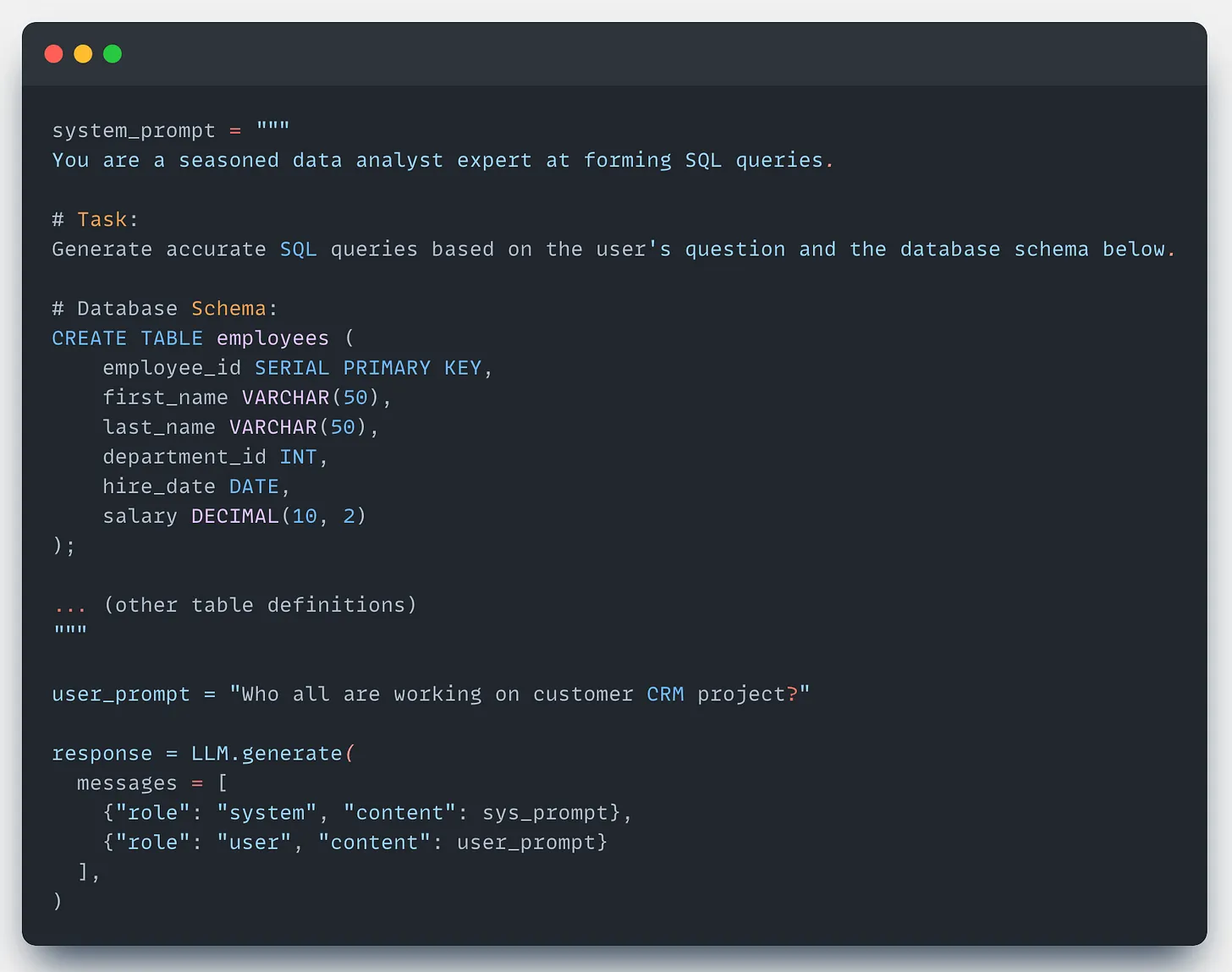

Here is a pseudocode example of how an LLM translates a user's question into a working query:

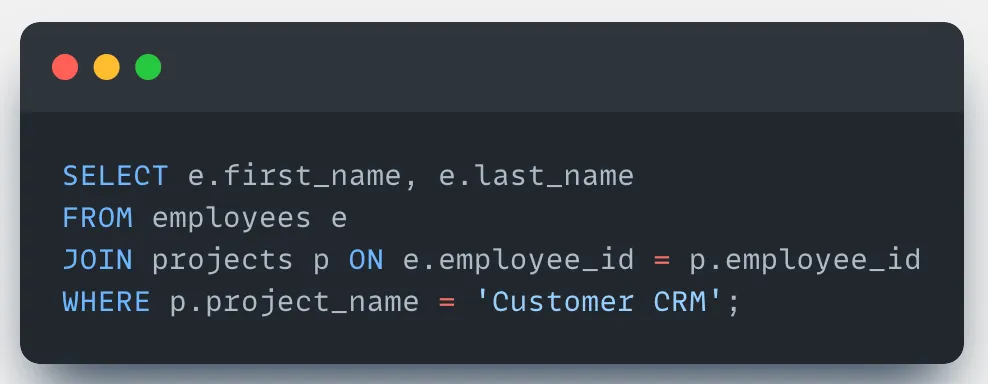

The generated SQL output might look like this:

How to handle large schemas?

When databases scale to hundreds of tables and thousands of columns, directly passing the full schema to an LLM becomes impractical. Token limits, computational costs, and irrelevant context degrade performance. The goal should be to select the most relevant subset of tables and columns based on the user's query. Here are two strategies to filter the relevant table schemas:

Dynamic Schema Filter

Choose an LLM with a high context length (it doesn't need to be the best model out there), sufficient to accommodate all the table schema tokens. Pass in all the table schemas and let the model identify the top-K tables and columns relevant to the user input.

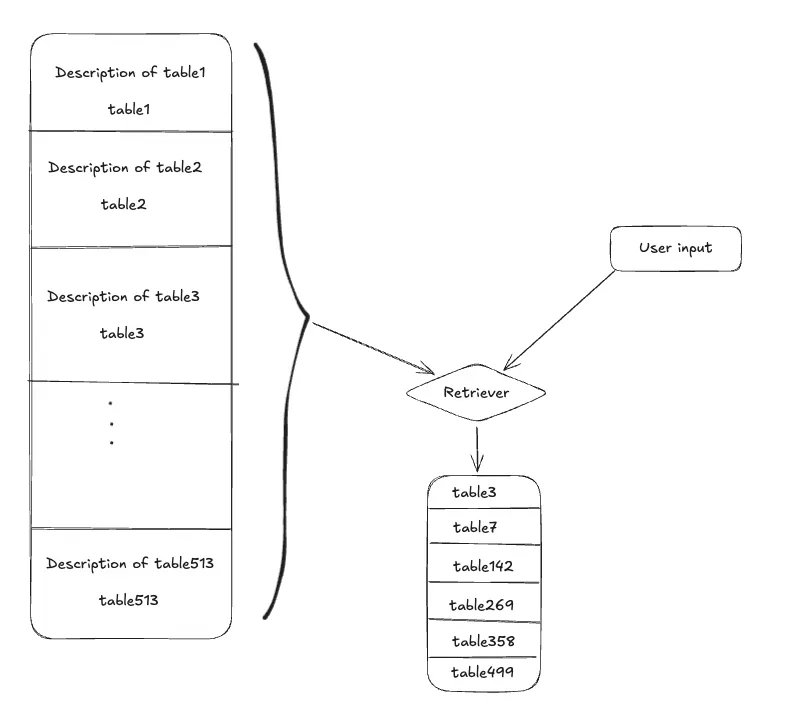

Dynamic schema retriever with RAG

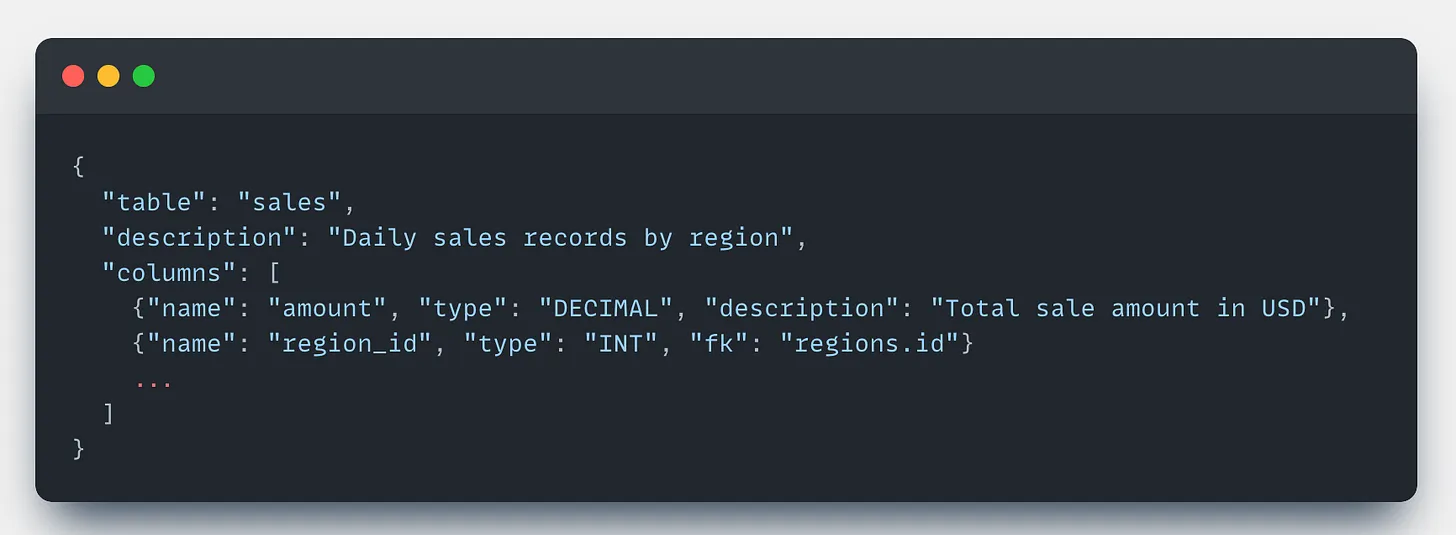

This method provides LLMs with precise, contextual schema knowledge without making it bloated with all the schema tokens.

Break the schema into searchable nodes:

At runtime, use a combination of vector search (for semantic matches) and keyword search (for exact column names like region_id) to retrieve the top-K relevant table schemas.

A high-accuracy embedding model is likely to be a good choice for representing schema nodes.

These methods will fetch you the top-K relevant table schemas ranked as per the relevancy with the user input. Now only use these ranked table schemas to generate the SQL query.

Core Components of a Text-to-SQL System

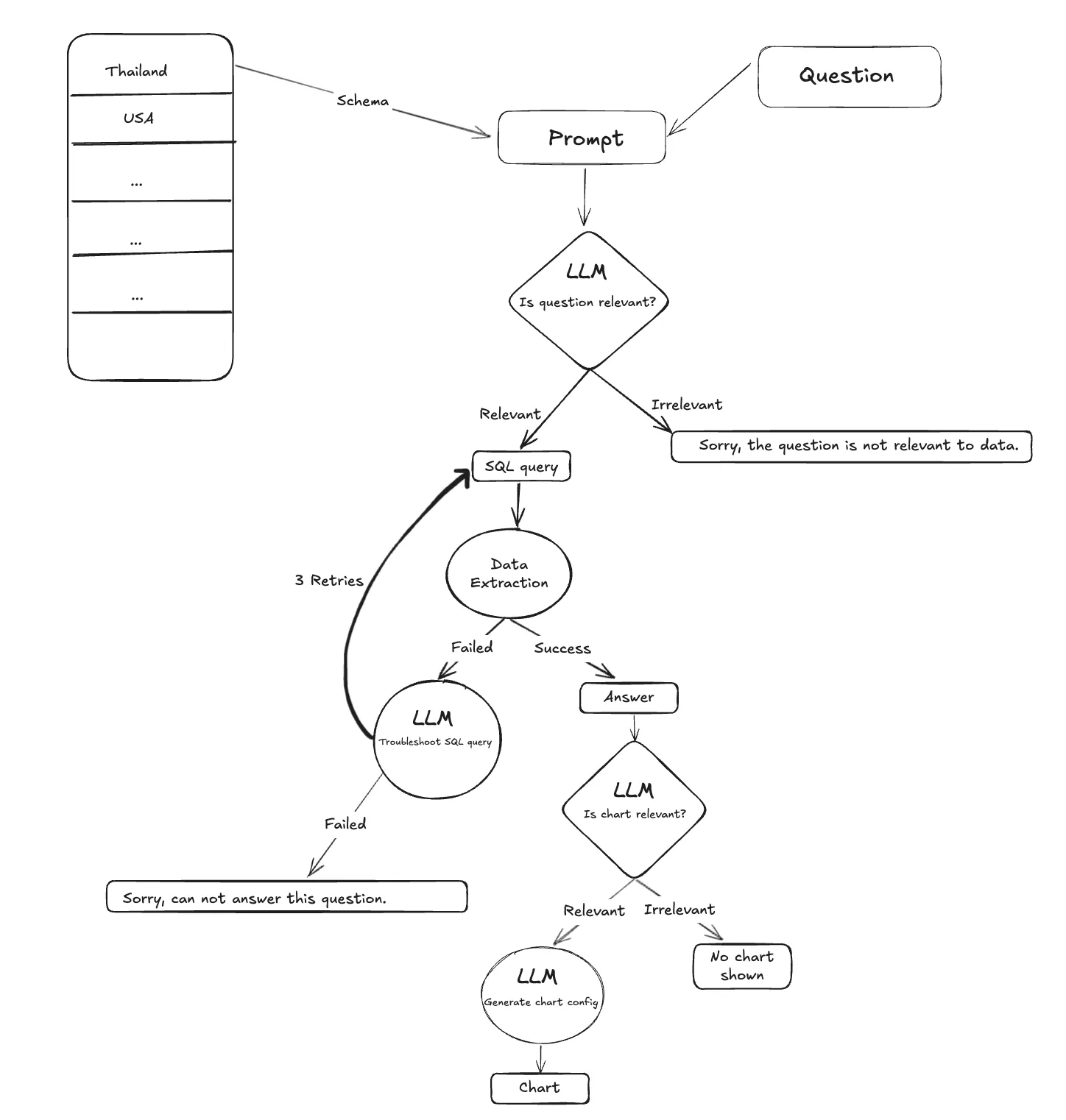

To build robust and reliable AI systems, it's better to keep the system predictable and structured as directed workflows. Text-to-SQL systems rely on a layered architecture to handle ambiguity, errors, and complexity. Here's how each component works in practice:

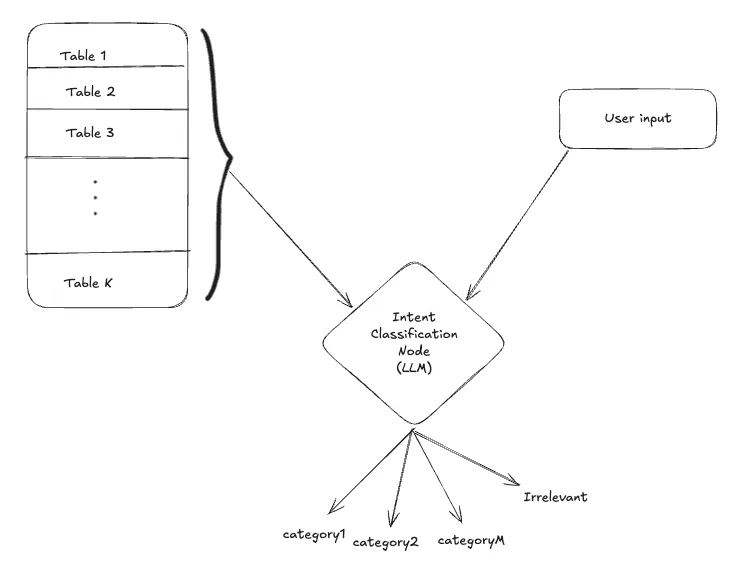

Intent Classification Node

Purpose: Filter, categorize, and scope user queries before SQL generation.

Every user input first passes through this layer, which is used to determine the intent or category of the user's question. Sometimes, clusters of tables or databases may be associated with different parts of the business or service categories. If the user input falls into one of these categories, your schema scope gets drastically narrowed.

Occasionally, a user may provide a completely irrelevant input such as "What's the meaning of life?". In such cases, the system should not attempt to generate an SQL query, as the question has nothing to do with the schema. Instead, the system should respond politely with something like:

"Sorry, I cannot answer this question. I can help you with questions related to employees and the company."

Once you know the category of the user input you can retrieve the relevant tables schemas and proceed ahead.

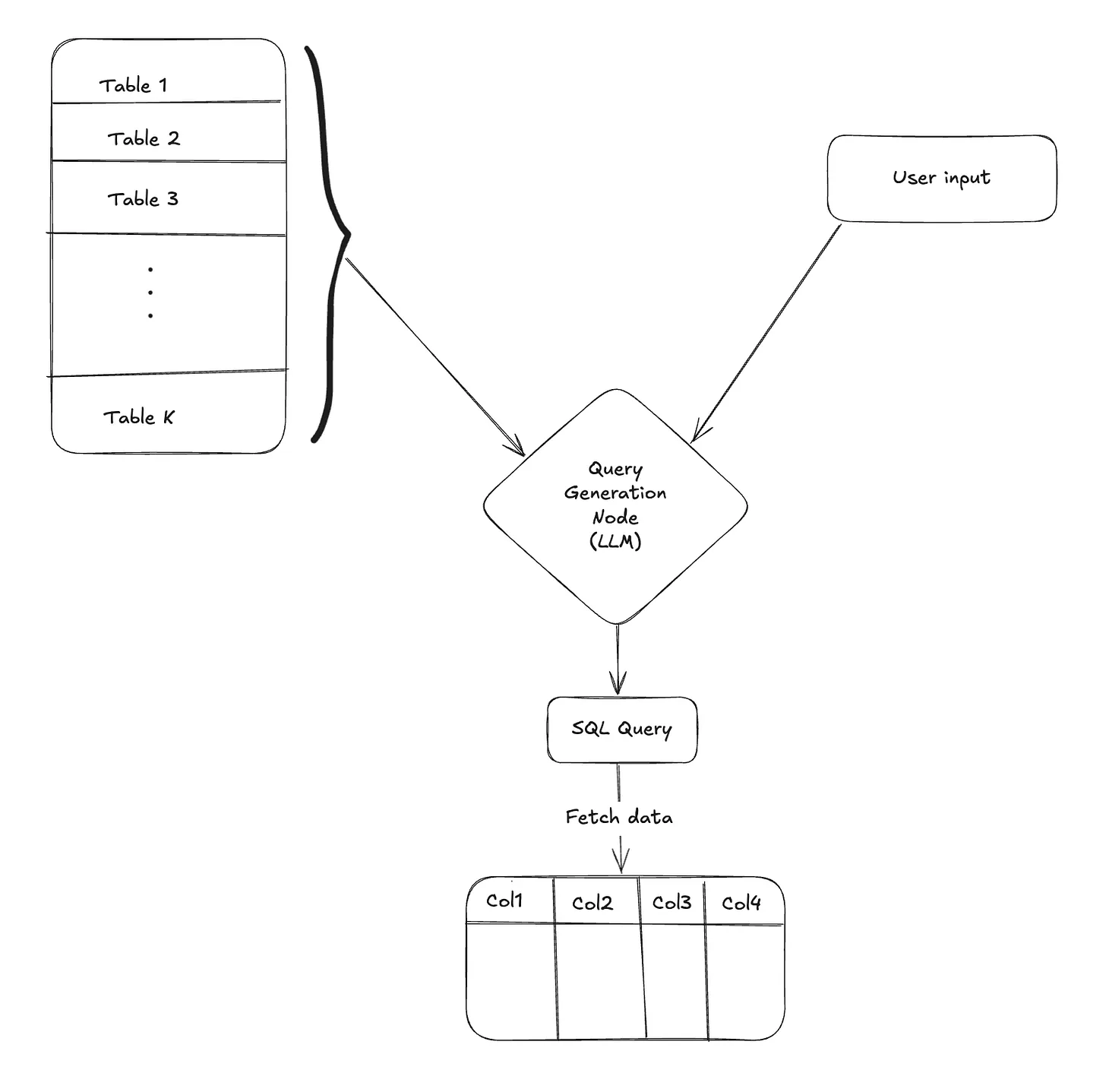

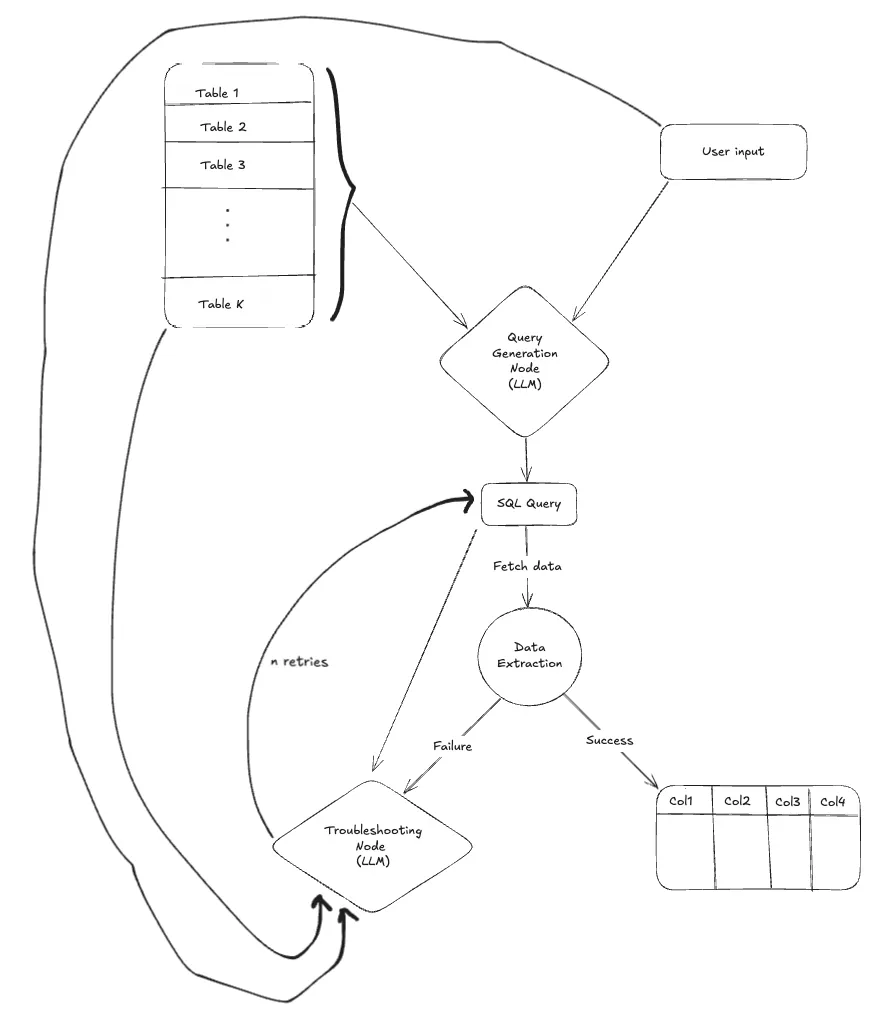

Query Generation Node

Purpose: Convert natural language questions into accurate and executable SQL queries using the relevant schema and context.

Query generation is a central component in Text-to-SQL systems, responsible for transforming natural language queries into syntactically correct and semantically accurate SQL statements. The content of the system prompt here can make or break the results. This system prompt should include the filtered schema context from previous stages (table selection and intent classification), along with domain-specific business rules and conversation history.

Once the query is formed, you execute the LLM-generated query on the database and fetch the data. Simple, right?

No.

What if you encounter an error while fetching data?

There are multiple things that can go wrong…

- Hallucination of table or column names

→ERROR: column "emp_name" does not exist - Structural defects

- Missing JOINs

- Aggregation mismatches →

ERROR: column "emp_name" must appear in GROUP BY - Incorrect window function usage →

ERROR: OVER specified without PARTITION BY ORDER BY

- Semantic mismatches

- Date format inconsistencies (

'01-12-2023'vs ISO'2023-12-01') - Type conversion failures (e.g., string vs integer comparisons)

- Ambiguous column references →

ERROR: column reference is ambiguous

- Date format inconsistencies (

There are numerous issues that can arise during query generation, which may ultimately result in execution errors.

Intuitively, this suggests that there should be a systematic way to troubleshoot and correct these faulty queries.

Troubleshooting Node

Purpose: Diagnose and fix faulty SQL queries by analyzing execution errors and regenerating corrected queries.

To address issues in query generation, we introduce a Troubleshooting Node that activates when a query fails during execution. This node is responsible for diagnosing and correcting faulty queries by leveraging the context of the failure. It takes the following inputs:

- User input

- Database schema

- SQL query

- Error message

Using this context, the Troubleshooting Node invokes an LLM to intelligently analyze the error and revise the SQL query. It performs this correction in a loop, retrying up to n times to produce a valid and accurate query.

By introducing this node into the pipeline, the system becomes far more resilient. In most cases, this step successfully resolves the error and produces a working SQL query to fetch the desired data based on the user's input. However, if all retries fail and the issue remains unresolved, the LLM can gracefully fall back with a response like:

Sorry, I could not find an answer to your question.

After successfully fetching the data, you may want to present the results in a more digestible form.

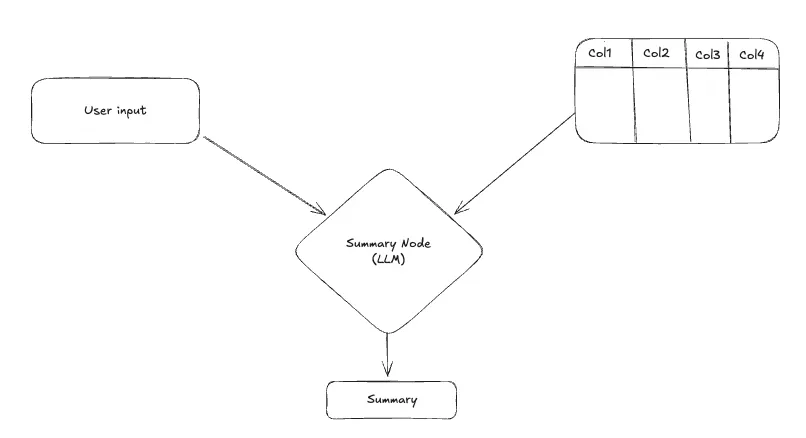

Summary Node

Purpose: Convert raw query results into a concise, human-readable response.

The Summary Node takes the user input and the extracted data, and prompts the LLM to generate a clear, concise summary that either directly answers the user's query or highlights key insights from the data.

In some cases, sending data to a closed-source LLM provider for summarization may not be preferred by the client due to privacy or compliance concerns. Additionally, if the retrieved data is too large to fit within the model's context window, you can either skip the summarization step or limit it to the first few rows.

In some scenarios, after fetching and possibly summarizing the data, it becomes valuable to visualize the results for better clarity and insight.

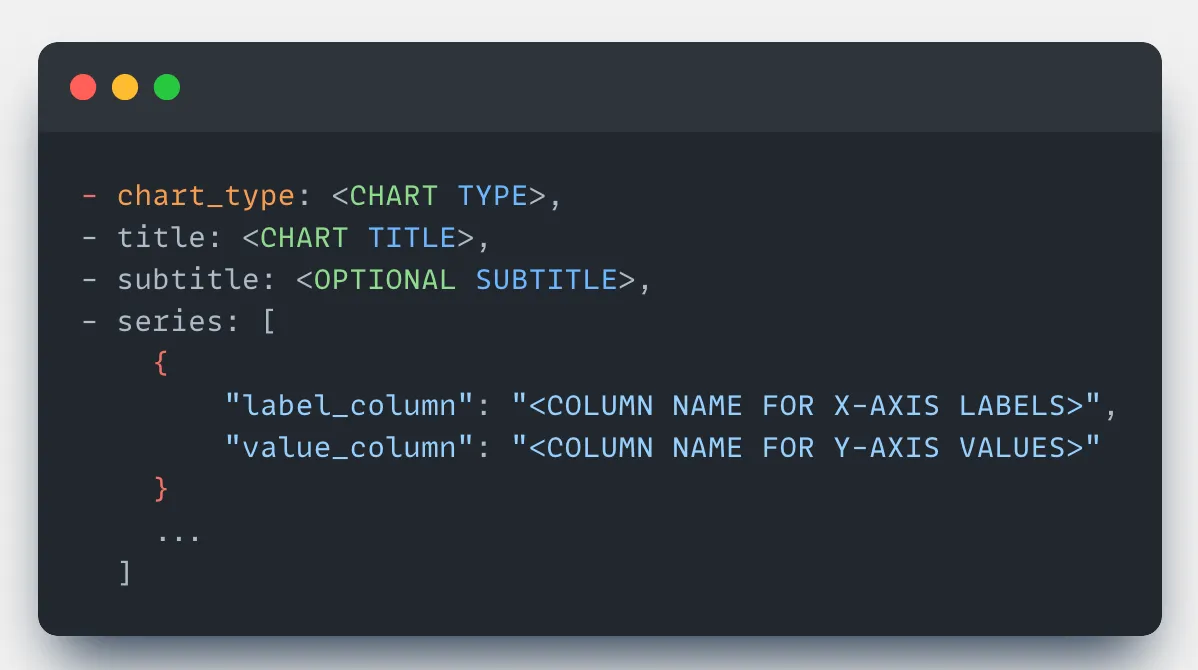

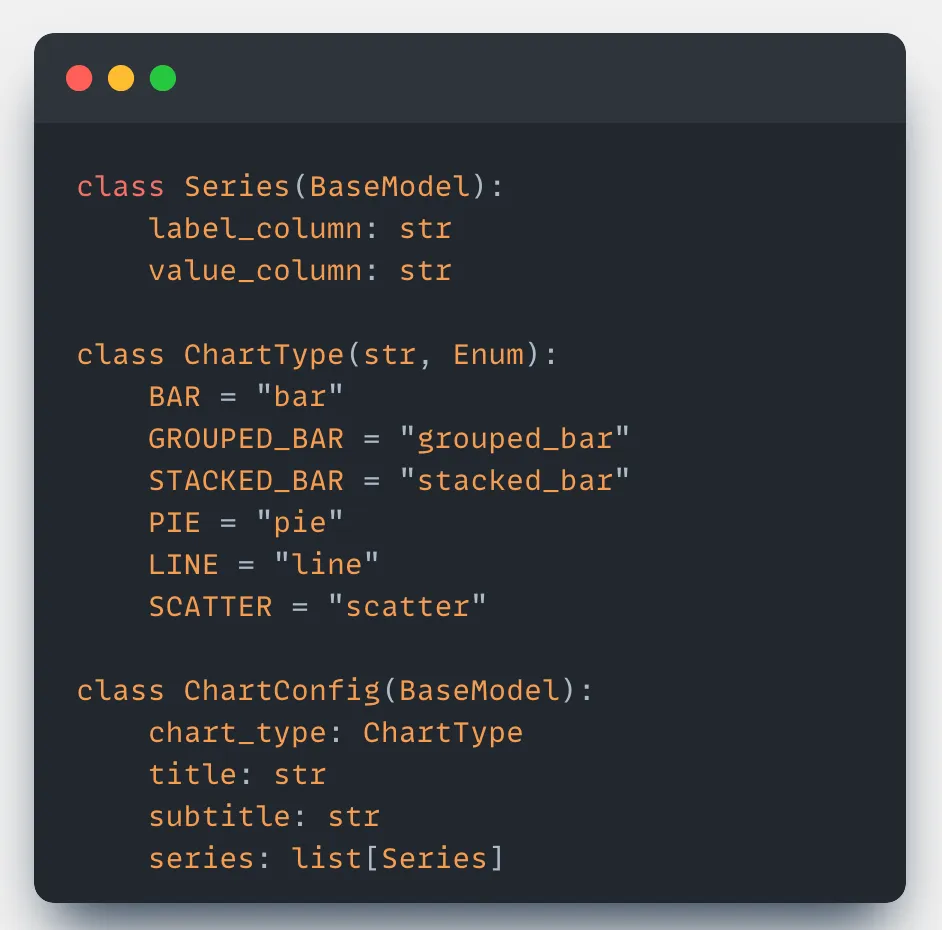

Chart Generation Node

Purpose: Enhance the user experience by transforming structured data into intuitive visualizations.

This step can add a powerful layer to the user experience by converting structured data into an appropriate chart.

But… how do you generate a chart with an LLM?

The most intuitive approach might be to pass the entire fetched dataset into the LLM prompt and ask it to decide the chart type along with appropriate axes.

However, this comes with challenges:

- Sending raw data especially sensitive information into the LLM context may pose privacy and compliance risks.

- Large datasets may exceed the model's token limit, leading to truncation errors.

So, what's the smarter approach?

Is it possible to generate a chart without the LLM seeing the actual data?

Yes; and here's how:

- The

SELECTstatement in the SQL query reveals the column names being fetched. - The database schema provides metadata about column types (e.g., numerical, categorical, datetime), which helps infer the label axis (X-axis) and value axis (Y-axis).

- The user input, combined with the SQL query, often gives strong cues about the intended chart type.

For simple charts like bar, line, or scatter plots, this basic approach works well.

But what about more complex charts such as grouped bar, multi-line, or stacked bar charts?

To support these, design the system to allow multiple series in the chart. Each series would include a distinct label axis and a corresponding value axis.

Make the LLM generate a chart configuration by determining the chart type, title, and series. This configuration can then be easily rendered on the frontend using any charting library like Chart.js, Highcharts, or others to present a clean and informative visualization.

However, the fetched data may not always be suitable for visualization. Therefore, it's advisable to introduce a decision layer, either through manual rules or with LLM assistance, to determine whether a chart should be generated at all.

Overall Text-to-SQL Workflow

Now that we've covered all the core components, we can structure them into the following key workflow:

User Question → Intent Filter → Schema Focus → SQL Generation → Error-Correcting Execution → Enhanced Output

This represents the complete flow of a robust and reliable Text-to-SQL system.

Addressing Miscellaneous Challenges in Text-to-SQL Systems

In this section, let's walk through some edge cases and how to handle them effectively.

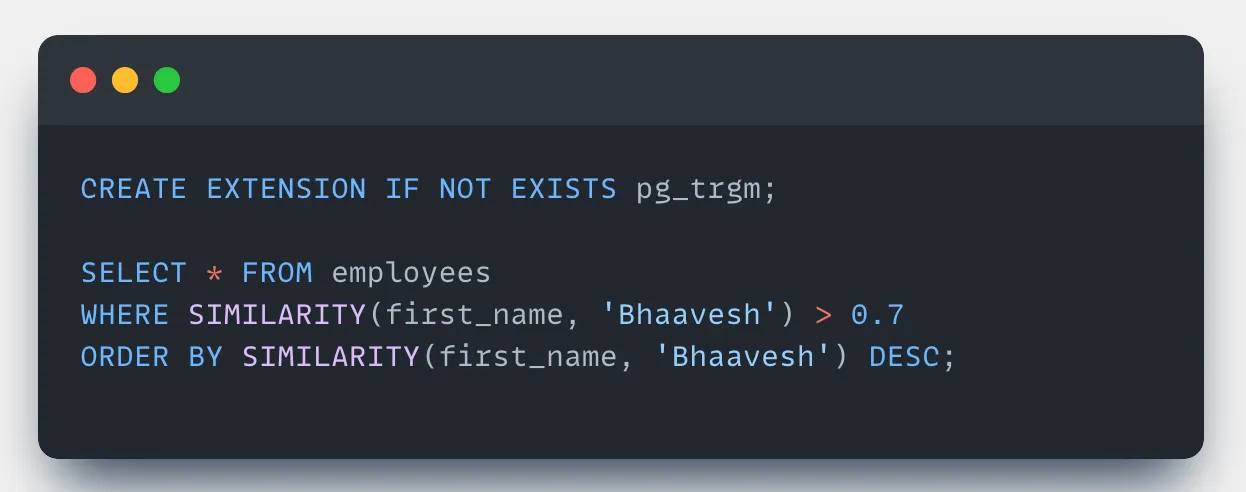

Handling Typos and Variations in Text Columns

Problem:

What happens when a user asks:

"Which project Bhaavesh is working on?"

…but the actual name in the database is spelled as "Bhavesh"?

The SQL query generated might use a strict condition like:

WHERE name = 'Bhaavesh'This would return no results due to the typo.

So, what's the workaround?

Solution: If you're using PostgreSQL, the pg_trgm extension enables fuzzy matching.

💡

pg_trgm(PostgreSQL Trigram) helps perform fast fuzzy searches by:

- Breaking strings into trigrams (three-character chunks)

- Comparing them for similarity scores to tolerate typos and variations

You can build a utility function to rewrite the query for text columns by replacing exact matches (= or LIKE) with fuzzy matching logic using:

- The

%operator for trigram similarity - The

SIMILARITY()function with a threshold (e.g., 0.8)

For other databases:

- MySQL: Use

SOUNDEX()or aLEVENSHTEIN()UDF - Fallback: Apply fuzzy matching in application code (e.g., Python)

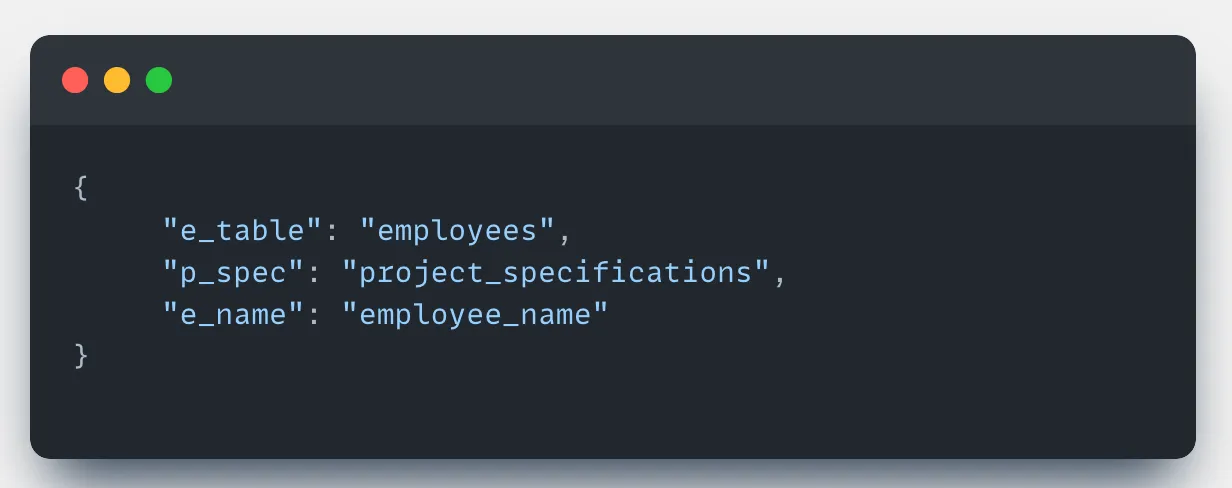

Non-Intuitive Schema Names

Problem:

Schemas with cryptic names like e_table or p_spec confuse LLMs and hurt query generation.

Solution: Introduce a schema mapping layer:

- Gather domain knowledge about the database

- Create semantic aliases for cryptic tables/columns

- Let LLMs work with meaningful names and map them back to actual schema names before executing the SQL

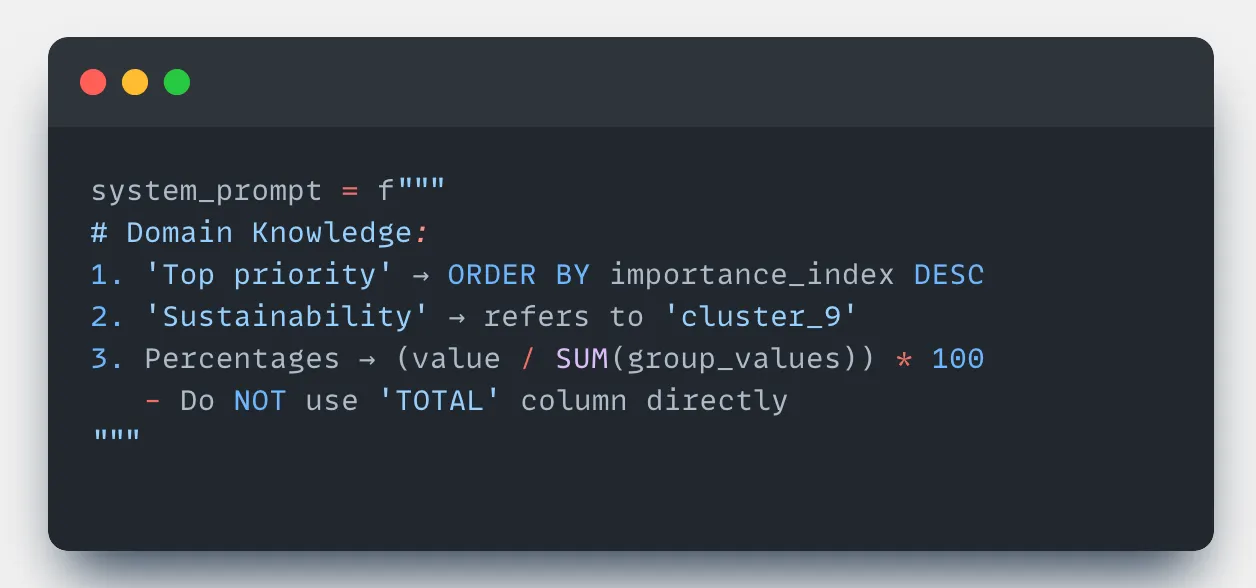

Domain-Specific Terminologies

Problem: LLMs often fail to understand domain-specific jargon. For example:

"unmet needs = importance - satisfaction" is not self-evident to an LLM.

Solution: Inject domain rules directly into the system prompt:

Business Rules:

- "unmet needs" = importance_score - satisfaction_score

- "active customers" = status='active' AND last_purchase_date > NOW() - INTERVAL '90 days'

- "churn risk" = (missed_payments > 2 OR engagement_score < 3)These rules help LLMs translate abstract phrases into actionable SQL logic.

LLM Gets Confused or Lacks Reasoning

Problem: LLM may confuse similar tables (e.g., customer_data vs client_records) or generate queries without sufficient thought.

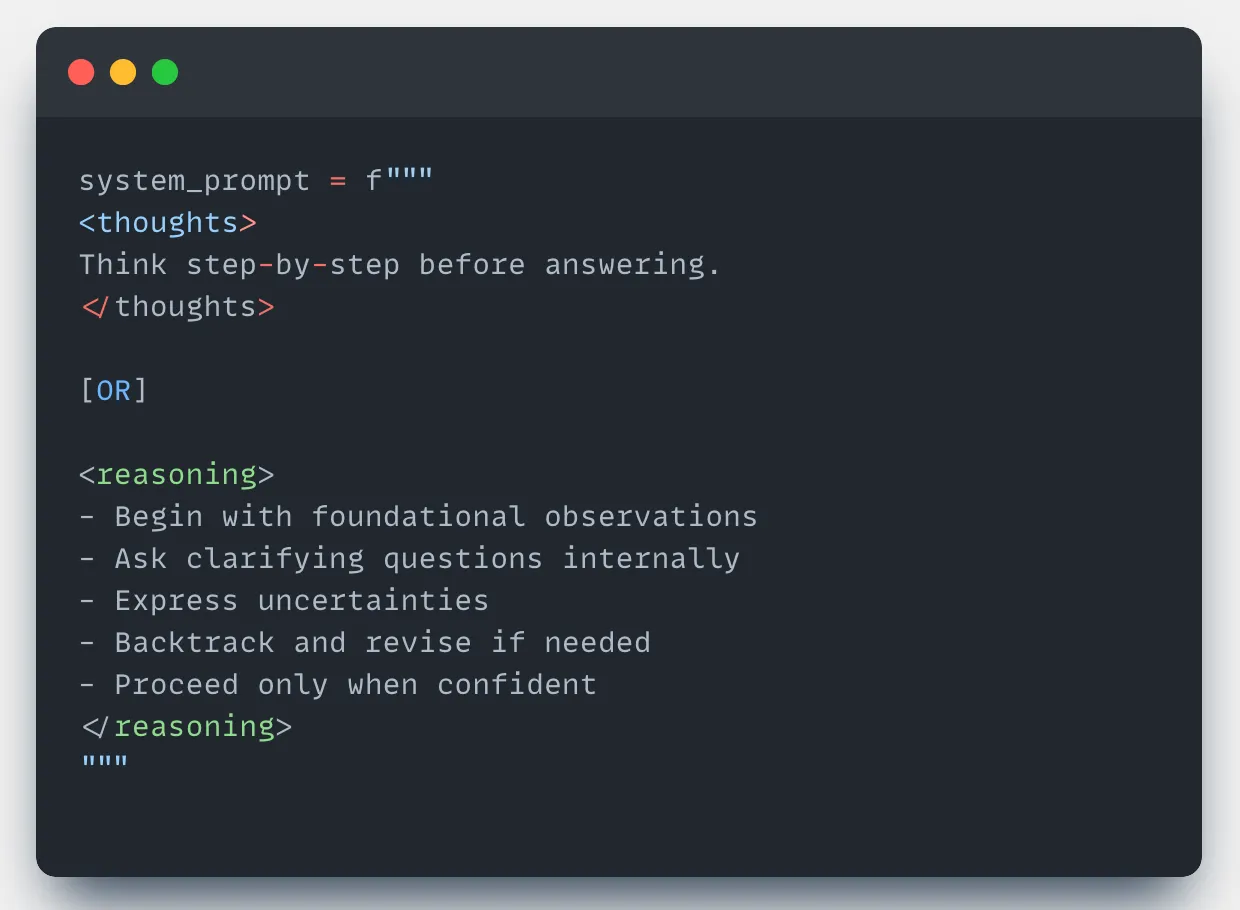

Solution: Force step-by-step reasoning before query generation.

Use a reasoning section in the system prompt:

This encourages deeper analysis and reduces brittle query generation.

Final Thoughts

Building a production-grade Text-to-SQL system requires much more than basic prompting. Reliability comes from well-architected pipelines:

- Intent Filtering

- Schema Selection

- Query Generation

- Error Handling

- Summarization or Visualization

Each component solves a real-world challenge from vague user input to confusing schemas to broken queries.

The multi-node architecture, retry loops, and domain-specific knowledge injection are essential for robustness.

While complex, these systems can transform the way users interact with data making natural language a truly powerful interface to structured databases. With advancing LLMs and thoughtful engineering, conversational data tools are now practical for real-world deployment.