In this post, we will understand and implement the transformer architecture behind GPT from scratch using good old Numpy!

We have all witnessed the magic of ChatGPT. Large Language Models (LLMs) consist of layers of GPTs (Generatively Pre-trained Transformers) stacked in sequence, with billions or even trillions of parameters trained on hundreds of gigabytes of text.

The transformer architecture was first introduced in this paper by Vaswani et al. for machine translation tasks. However, in GPTs, only the decoder part of the transformer is used. Transformers are a type of machine learning model primarily used for processing language. Imagine you have a huge book and you want to understand its content without reading every word. Transformers can achieve this by analyzing different parts of the text and determining the relationships between words and phrases. They use a mechanism called "attention" to focus on the important parts of the text, making them very effective at tasks like translating languages, summarizing articles, or even chatting with you. Transformers learn from extensive text data, improving their ability to understand and generate human-like text over time.

Note: This post assumes familiarity with Python, Numpy, PyTorch, some past experience with neural networks, and a good dose of curiosity.

We will implement all the components of the Transformer architecture using plain NumPy.

We are only going to understand and implement the architecture from scratch but not dive into the training or inference part of a language model as that will be beyond the scope of this blog post.

How to Feed the Text In?

When you type text into ChatGPT, it is fed into the model as a sequence of numbers. Imagine you have a sentence—let's say, "The cat chased the mouse." In the world of computers, understanding this sentence isn't as straightforward as it is for humans. That's where tokenization comes in.

Tokenization is the process of breaking down the text into smaller, more manageable units called tokens and mapping each one of them to a unique integer. This is typically achieved using specialized tokenizers. These tokens collectively form a vocabulary, where each word in the vocabulary is mapped to an integer.

input = ["the", "cat", "chased", "the", "mouse"]

| | | | |

[ 3 , 7 , 0 , 3, 5 ]

Advanced tokenization goes beyond simple word and whitespace splitting, involving complex methods to form tokens and often resulting in a large vocabulary. Examples of such methods include Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) and WordPiece.

We will be using OpenAI’s tiktoken library for BPE tokenization.

You can install it with

!pip install tiktoken

import tiktoken

tokenizer = tiktoken.encoding_for_model("gpt-2")

tokens = tokenizer.encode("the cat chased the mouse").

# [1169, 3797, 26172, 262, 10211, 13]

text = tokenizer.decode(tokens)

# the cat chased the mouse

To see how the text tokens are splitting in our case with tiktokens Byte-pair encoding model.

token_strings = [enc.decode([token]) for token in tokens]

# ['the', ' cat', ' chased', ' the', ' mouse', '.']

As can be seen, whitespaces are included with the words in some cases when forming tokens, and punctuation, such as the full stop, is treated as a separate token.

These integers are then associated with word embeddings. In short, a word embedding is a real-valued vector that encodes the meaning of a token and maps it to the embedding space among all the other tokens. This mapping is done in such a way that tokens with similar meanings are positioned close to each other in the embedding space.

The representation of vector embedding space can be understood with the following example:

If we map the words king, queen, man, and woman in the embedding space and perform vector algebra, it will look something like this:

queen - woman + man ≈ king.

In the Transformer architecture, there is an additional type of embedding known as positional embeddings. Normal text embeddings do not account for the position of the token in the sequence. This would cause problems in next-token prediction because, if we randomly shuffle the words in the input sequence, the output sequence would not be affected. To address this, we use text + positional embeddings.

The embedding function is essentially a table that maps the token sequence to the n_embd space.

To see how the text tokens are splitting in our case with tiktokens Byte-pair encoding model.

def embedding(vocab_size, embedding_dim):

embedding = np.zeros((vocab_size, embedding_dim))

return embedding

The text embeddings are converted to n_embd space like follow

text_embeddings_table = embedding(vocab_size, n_embd)

input = [1169, 3797, 26172, 262, 10211, 13] # ['the', ' cat', ' chased', ' the', ' mouse', '.']

text_embd = text_embeddings_table[input] # [n_seq] -> [n_seq, n_embd]

text_embd # (6) -> (6, n_embd)

For generating positional embeddings, the maximum length of the input sequence should be defined, just like the vocab_size in the case of generating text embeddings.

pos_embeddings_table = embedding(max_len_seq, n_embd)

input = ['the', ' cat', ' chased', ' the', ' mouse', '.']

pos_embd = text_embeddings_table[range(len(input))] # [n_seq] -> [n_seq, n_embd]

pos_embd # (6) -> (6, n_embd)

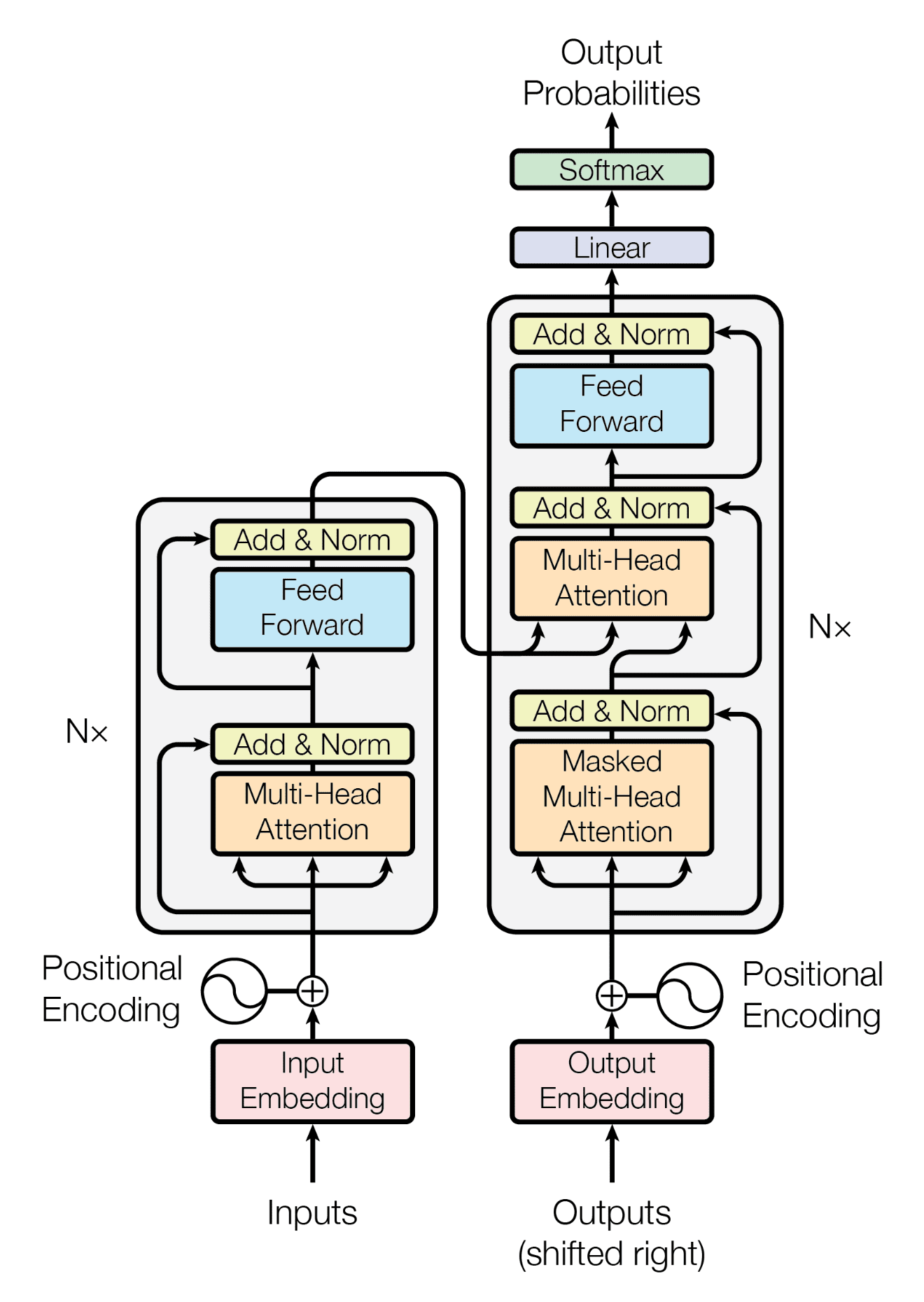

The transformer architecture, as described in the original paper, looks like this diagram:

The Transformer Architecture

The Transformer Architecture

I know, that seems heavy to digest! But don't worry, we'll break it down into bite-sized pieces that are easier to understand. Before we go into the secret ingredient that makes transformers so powerful—the self-attention mechanism—let's first explore the fundamental layers that lay the groundwork for this architecture. By understanding these building blocks, you'll have a solid foundation to grasp the inner workings of transformers. So, let's roll up our sleeves and get started!

Linear

A linear layer is often referred to as a projection from one vector space to another vector space. It allows the model to learn and adapt during the forward propagation process by adjusting its weights and biases.

def linear(input, weight, bias=None):

output = np.dot(input, weight.T)

if bias is not None:

output += bias

return output

The function linear acts same as nn.Linear() in pytorch.

>>> x = np.random((8, 128)) # 128 dimensioned input vector of batch size 8

>>> w = np.random((128, 256)) # weight vector for projecting x into 256 dim space

>>> b = np.random(256) # bias for the projected vector

>>> y = linear(x, w, b)

>>> y.shape # shape after linear projection

(8, 256)

Softmax

\( \text{softmax}(x)_i = \frac{e^{x_i}}{\sum_j e^{x_j}} \)

Softmax is a function often used in the output layer of a neural network for multi-class classification problems. Its purpose is to turn a vector of real numbers into a vector of values between 0 and 1 that add up to 1. This way, the output can be interpreted as a probability distribution over the classes.

def softmax(input):

return np.exp(x) / np.sum(np.exp(x))

The function is simple emulation of nn.Softmax() in pytorch.

>>> x = np.array([[3, 40, -20], [-50, 0, 30]])

>>> y = softmax(x)

>>> y

[[8.53266024e-17 9.99954602e-01 8.75611324e-27]

[8.19364063e-40 4.24816139e-18 4.53978687e-05]

>>> Y.sum(axis=-1)

array([1., 1.])

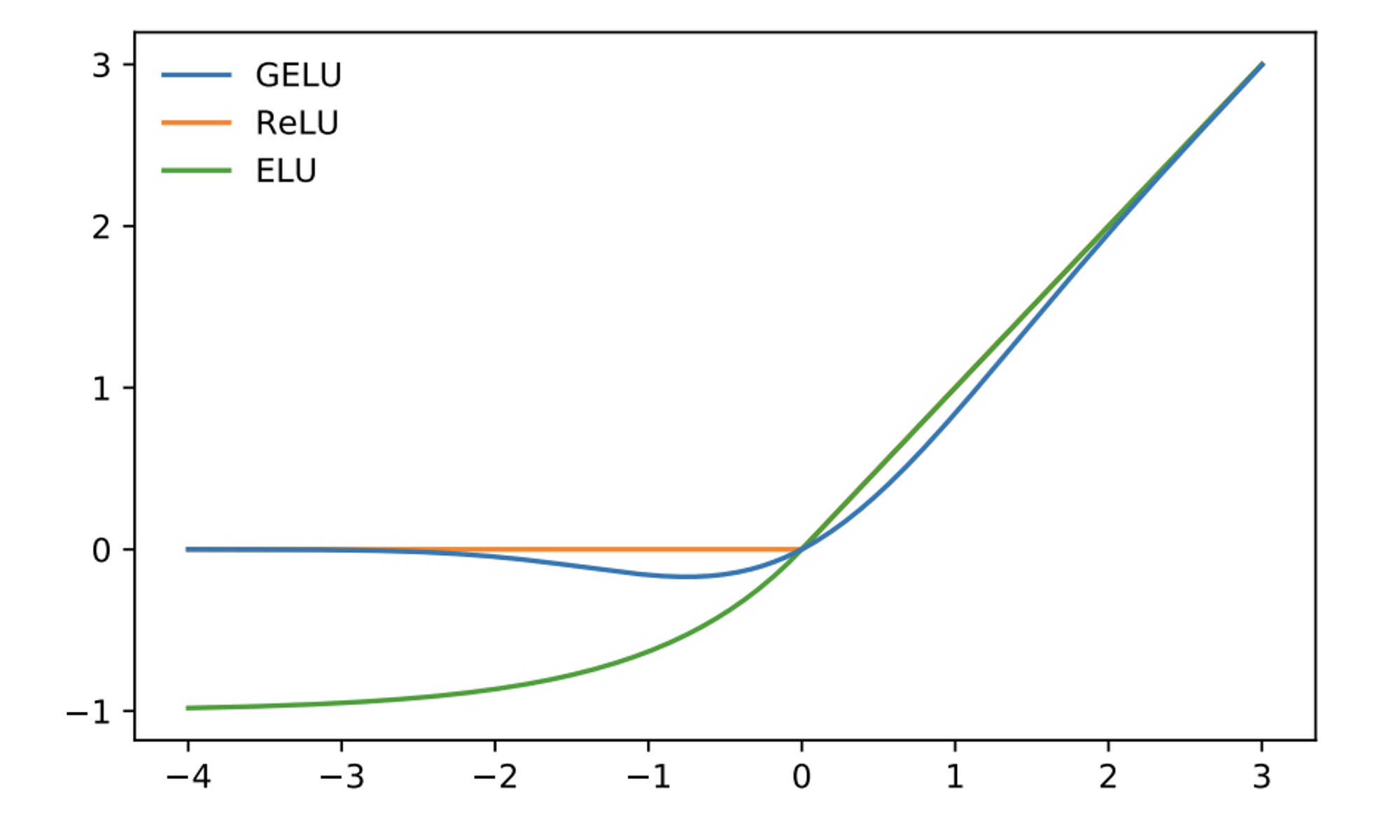

GELU

GELU (Gaussian Error Linear Unit) is an activation function used in deep neural networks, particularly in transformer architectures. The idea behind GELU is to combine the properties of the ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) and the Gaussian distribution.

Activation of GELU from original paper

Activation of GELU from original paper

The function is linear for positive inputs, similar to ReLU, which helps mitigate the vanishing gradient problem. For negative inputs, GELU has a smooth, non-linear shape based on the cumulative distribution function of the Gaussian distribution. This shape allows the function to capture more complex patterns in the data.

def gelu(input):

return 0.5 * x * (1 + np.tanh(np.sqrt(2 / np.pi) * (x + 0.044715 * np.power(x, 3))))))

The gelu we implemented is similar to nn.GELU() in pytorch.

>>> x = np.array([1.0, -2.0, 3.0])

>>> y = gelu(x)

>>> y

array([ 0.84119199 -0.04540231 2.99636261])

Layer Norm

Layer normalization works by scaling the inputs to have resulting mean 0 and a variance of 1.

$$\begin{align*} \text{LayerNorm}(x) &= \gamma \left( \frac{x - \mu}{\sqrt{\sigma^2 + \epsilon}} \right) + \beta \end{align*}$$

There are two learnable parameters in the equation. The gamma scales the normalized input and beta adds the offset. ϵ is a small constant to avoid division by zero.

def layer_norm(x, gamma, beta, epsilon=1e-5):

mean = np.mean(x, axis=-1, keepdims=True)

variance = np.var(x, axis=-1, keepdims=True)

normalized_x = (x - mean) / np.sqrt(variance + epsilon)

return gamma * normalized_x + beta

Layer norm is preferred choice over BatchNorm in transformer architecture. Our function layer_norm works the same way nn.LayerNorm() works.

>>> x = np.array([[2, -3, 9, 4], [3, 60, 8.34, -34], [-8, -98, 0.35, 8]])

>>> y = layer_norm(x, gamma=np.ones(x.shape[-1]), beta=np.zeros(x.shape[-1]))

>>> y

array([[-0.23249521, -1.39497129, 1.39497129, 0.23249521],

[-0.18916798, 1.51289591, -0.02971147, -1.29401647],

[ 0.38292437, -1.71688941, 0.57774043, 0.7562246 ]])

Attention is all you need!

The secret sauce behind the working of transformers is self-attention. When you pass in a sequence of words into the transformer, self-attention allows the model to weigh the importance of different words in a sentence when processing each word. Imagine you're reading a sentence and trying to understand the context of a particular word. Instead of just looking at the word itself, self-attention lets you look at all the other words in the sentence to decide which ones are most relevant to understanding that word.

Consider the statement: "I live in France and I speak ___." The most obvious filler for the blank is a language, and in this case, it would preferably be 'French.' The prediction of this filler is heavily influenced by the preceding context, specifically the mention of 'France' and the immediate preceding word 'speak'. The self-attention mechanism is a key component in transformer architecture that captures these intricate relationships among the text tokens.

Self-attention is like giving each word in a sentence a spotlight. Imagine you're reading a book and want to understand it really well. With self-attention, you focus not just on one word at a time, but on all the words together. Each word gets to influence how you understand the context. So, if "dog" is mentioned, it might pay more attention to "bark" or "pet" if they're in proximity. This helps in understanding the text better, especially in tasks like translation or summarization.

Let’s see in detail how self-attention works…

Each token in the text emits three vectors for information retrieval and processing:

- Query: This serves as a reference criterion guiding the attention mechanism to focus on specific aspects of the other tokens. It consists of the information that a particular token seeks to retrieve from other available tokens.

- Key: This serves as an index or identifier associated with that particular token. It provides a means for the attention mechanism to match relevant information to the query. Keys encode distinctive features or characteristics of the input elements.

- Value: This corresponds to the actual content used for the information processing associated with each token. It retrieves the data that the model retrieves based on the query-key matching. Values encapsulate the context or the relevant information for the particular token.

As per the very intuitive analogy by Andrej Karpathy in this video, the Query vector for a given token in the context of the entire text can be thought of as "What am I looking for?" For example, if the given token is a vowel, it is most likely searching for a consonant. The Key vector can be thought of as "What do I contain?" The Value vector can be considered as "If you find me interesting, here is what I will communicate to you."

The attention mechanism computes the similarity between the query \( q_i \) and each key-value pair \( (k_i, v_i) \). This similarity score determines the importance or weight assigned to each key-value pair. Subsequently, the mechanism generates an output by aggregating the values, weighted by their corresponding similarity scores as formulated in the equation below.

Keeping the explanation in mind, the mathematical formula for attention is defined as follows:

$$\alpha_i = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{q \cdot k_i}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)$$

$$\text{Output} = \sum_{i} \alpha_i v_i$$

In the equation above, how did softmax and \( \frac{1}{\sqrt{d_k}} \) make it into the formula?

- The introduction of softmax ensures that attention weights sum up to 1, allowing effective distribution of attention across all key-value pairs. It makes the outputs probabilistic in nature and ensures differentiability, which is essential for back-propagation during training.

- Scaling by \( \frac{1}{\sqrt{d_k}} \) stabilizes the gradients during training by preventing them from leaning towards either extreme of 0 and 1, ensuring stable training. It ensures that the softmax function is not too concentrated or too spread out, which can lead to vanishing gradients. It can also be thought of as a regularizer that controls the magnitude of the dot product from becoming too large.

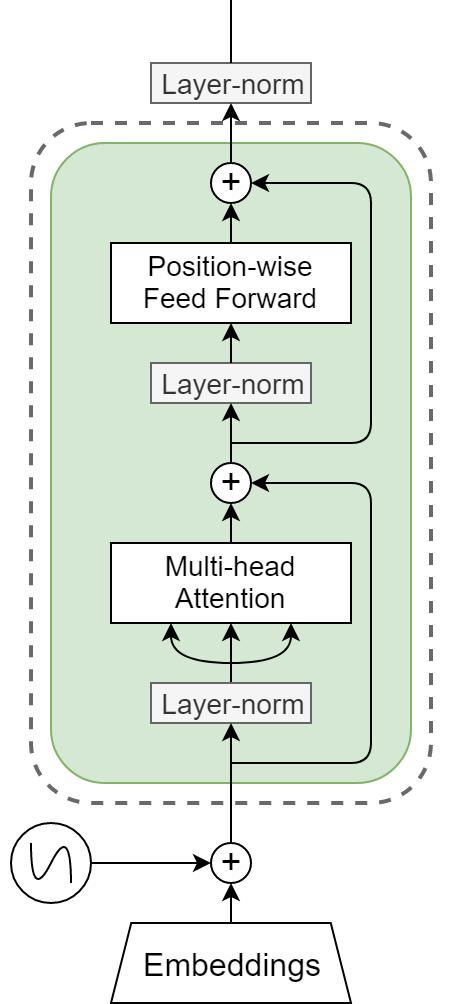

However, the transformers in GPTs consist of only the decoder stack of the above encoder-decoder architecture. We also don’t utilize the cross-attention formed between the encoder stack and decoder stack.

Essentially, our architecture becomes:

Decoder only part of transformer

Decoder only part of transformer

One self-attention mechanism is referred to as a single attention head. The transformer utilizes multi-head attention, which consists of multiple self-attention mechanisms working in parallel. Multi-head attention can be analogized to the multiple convolution filters in Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). The multi-head attention allows the model to attend to different parts of the input sequence simultaneously, capturing various relationships and dependencies.

The head size determines the dimensionality of the learned attention weights within each head. It is a hyperparameter that you can set when designing your transformer model. Essentially, the head size controls the capacity and expressiveness of each attention head.

Here's a simple breakdown of how it works:

- The input sequence is first transformed into query, key, and value vectors.

- These vectors are then split into multiple heads, each with a dimensionality equal to the head size.

- Within each head, the attention weights are computed based on the query, key, and value vectors.

- The attention weights are used to weigh the importance of different positions in the input sequence.

- The outputs from all the heads are then concatenated and transformed to produce the final output of the multi-head attention layer.

To start coding the GPT architecture, let’s list down the components present:

- Text + Positional Embeddings

- Softmax

- LayerNorm

- Attention Block

- Multi-Head Attention

- Add & Norm (Residual Connections)

- Feedforward Block

- Projection Layer

As we are implementing the GPT-2 architecture from scratch, we will follow the exact same configuration.

# hyperparameters

n_embd = 768, # Dimensionality of the embeddings and hidden states

n_layer = 12, # Number of transformer blocks

n_head = 12, # Number of attention heads in each attention layer

n_positions = 1024, # Maximum number of positions in the input sequence

n_ctx = 1024, # Size of the context window for the attention mechanism

vocab_size = 50257, # Vocabulary size (number of tokens)

activation_function = "gelu", # Activation function used in the model

layer_norm_epsilon = 1e-5, # Epsilon used in layer normalization

layerwise_config = {

"wpe": [ # positional embeddings

1024, # max sequence length

768 # n_embd

],

"wte": [ # token embeddings

50257, # vocab size

768 # n_embd

],

"ln_f": { # pre layer norm

"b": [

768 # bias term shape

],

"g": [

768 # gamma term shape

]

},

"blocks": [ # list of transformer block. (multiple blocks in parellel in gpt)

{

"attn": { # attention block

"c_attn": {

"b": [

2304

],

"w": [

768,

2304

]

},

"c_proj": { # projection layer

"b": [

768

],

"w": [

768,

768

]

}

},

"ln_1": { # layer norm 1

"b": [

768

],

"g": [

768

]

},

"ln_2": { # layer norm 2

"b": [

768

],

"g": [

768

]

},

"mlp": { # multilayer perceptron block / feed forward network block

"c_fc": {

"b": [

3072

],

"w": [

768,

3072

]

},

"c_proj": { # final projection layer

"b": [

768

],

"w": [

3072,

768

]

}

}

}

]

}

So we will lay the foundation of the main GPT function and then proceed to implement the underlying components.

class GPT2:

def __init__(self):

self.token_emb = embedding(vocab_size, n_embd)

self.pos_emb = embedding(n_positions, n_embd)

self.transformer_blocks = [TransformerBlock(n_embd, n_head) for _ in range(n_layer)]

def forward(self, inputs):

# token + positional embeddings

x = self.token_emb[inputs] + self.pos_emb[np.arange(inputs.shape[1]) % n_positions]

# input sequence passing through 'n_layer' number of transformer blocks

for block in self.transformer_blocks:

x = block.forward(x)

# projection to sequence of words

x = x @ token_emb.T # [n_seq, n_embd] -> [n_seq, vocab_size]

return x

Now we start defining the elephant in the room: TransformerBlock.

class TransformerBlock:

def __init__(self, n_embd, n_head):

self.attn = MultiHeadAttention(n_embd, n_head)

self.ffn = FeedForward(n_embd)

self.ln1 = np.ones(n_embd), np.zeros(n_embd) # Gamma, Beta for LayerNorm

self.ln2 = np.ones(n_embd), np.zeros(n_embd)

def forward(self, x):

x = x + self.attn.forward(layernorm(x, *self.ln1))

x = x + self.ffn.forward(layernorm(x, *self.ln2))

return x

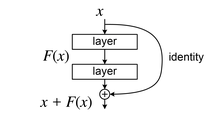

In the above code, we can see a type of skip connection taking place in the MultiHeadAttention and FeedForward blocks. These skip connections are called residual connections. These connections allow information to bypass layers and flow directly from earlier layers to later ones. During the training process, each layer of the transformer block learns to adjust the input data slightly, refining the representations formed by the previous layers. However, sometimes, the optimal output for a layer is close to its input data. In such circumstances, learning the identity function can be challenging for the layer.

Here, skip connections come into play. They allow the model to propagate information directly across multiple layers by skipping over some intermediate layers, thus creating a sort of "shortcut" in the network. When the output of a layer is added to its input, the layer only needs to learn the residual error between its output and its original input, hence the name "residual connections."

This mechanism significantly improves the model's ability to learn during the training process by mitigating problems such as vanishing and exploding gradients. These problems often occur in deep learning models, where the gradients used to update the model weights become too small (vanish) or too large (explode). By facilitating more effective information flow, skip connections help the model train faster and achieve better performance.

Residual connections

Residual connections, introduced in ResNet, have significantly improved the training of deep neural networks. These connections allow gradients, which are essential for adjusting the network during training, to flow more easily through the layers. By providing "shortcuts" for the gradients, residual connections make it easier to optimize the network, especially as it gets deeper. This ease of gradient flow ensures that the earlier layers in the network can be effectively trained, even in very deep architectures.

Residual connection in neural network

Residual connection in neural network

Moreover, residual connections help maintain and enhance the performance of deep networks. Without them, adding more layers to a model can lead to a degradation in performance, possibly because it's challenging for the gradients to travel back through all the layers without losing crucial information. Residual connections address this issue by allowing direct pathways for the gradients, supporting better learning and performance even as the network's depth increases.

In addition to aiding in optimization and performance, residual connections also tackle the vanishing and exploding gradient problems. These issues often arise in deep networks, where gradients can become too small (vanish) or too large (explode) during backpropagation, making the training process unstable. By facilitating a more stable gradient flow, residual connections help ensure that the network can train effectively without encountering these common pitfalls, leading to more accurate and reliable models.

Before we implement MultiHeadAttention and FeedForward, we need to implement the building block of multi-head attention, which is AttentionHead. These come together in parallel to form multi-head attention.

class AttentionHead:

def __init__(self, embd_size, head_size):

self.W_q = np.random.randn(head_size, embd_size)

self.W_k = np.random.randn(head_size, embd_size)

self.W_v = np.random.randn(head_size, embd_size)

self.tril = np.tril(np.ones((n_positions, n_positions)))

def forward(self, x):

q = linear(x, self.W_q)

k = linear(x, self.W_k)

v = linear(x, self.W_v)

k_transpose = k.transpose(0, 2, 1) # Transposing for proper matrix multiplication

wei = np.matmul(q, k_transpose) / np.sqrt(k.shape[-1])

wei = np.where(self.tril[:x.shape[1], :x.shape[1]] == 0, -np.inf, wei)

wei = softmax(wei)

out = np.matmul(wei, v)

return out

Well, that might seem a bit overwhelming to digest… so let’s break down what is happening in the code above.

- First, we define the weights for the Key, Query, and Value matrices in the constructor.

- Then, we define a lower triangular matrix with

self.tril.>>> array = np.array([[1, 2, 3, 4], [5, 6, 7, 8], [9, 10, 11, 12], [13, 14, 15, 16]]) >>> lower_triangular = np.tril(array) >>> print(lower_triangular) array([[ 1 0 0 0] [ 5 6 0 0] [ 9 10 11 0] [13 14 15 16]]) - This lower triangular matrix is used for masking future tokens. It ensures the model does not look ahead in the sequence while predicting the current token.

- In the forward function, we project the input by applying this mask of

self.tril. We set the upper triangular part of theweimatrix tonp.inf. This operation masks out future tokens, ensuring the model only attends to previous and current tokens.

But why?

Well, the GPT architecture we are implementing is also known as causal self-attention. The word causal here represents that the attention score for the current token is the result of the previously seen tokens. Hence, we mask all the future tokens while calculating the attention score for the current token at hand.

We will now go ahead and implement the MultiHeadAttention and FeedForward.

class MultiHeadAttention:

def __init__(self, embd_size, num_heads):

self.heads = [AttentionHead(embd_size, embd_size // num_heads) for _ in range(num_heads)]

self.proj = np.random.randn(embd_size, embd_size) # Correct projection matrix

def forward(self, x):

head_outputs = [head.forward(x) for head in self.heads]

concat = np.concatenate(head_outputs, axis=2)

return linear(concat, self.proj)

Multi-head attention consists of multiple attention layers running in parallel. Each layer, or "head," can focus on different parts of the input data. Each attention head learns to attend to different features of the input. For instance, in a language processing task, one head might focus on syntactic features, another on semantic context, and yet another on specific entities mentioned in the text. This diversity allows the model to capture a richer understanding of the input.

After the output from the multi-head attention is concatenated (combining outputs from all heads), it usually undergoes a linear transformation. This step mixes and compresses the different representational aspects captured by each head back into a unified embedding dimension.

Each transformer block contains a position-wise feed-forward network that applies further transformations to the linearly transformed attention outputs. This network typically consists of two linear transformations with a non-linearity (here, GELU) in between. The feed-forward network operates independently on each position of the sequence, ensuring that the model retains its ability to handle inputs of variable length without any positional biases affecting the transformations.

class FeedForward:

def __init__(self, n_embd):

# Adjust dimension order for weight matrices

self.W1 = np.random.randn(n_embd * 4, n_embd) # [output_features, input_features]

self.b1 = np.zeros(n_embd * 4)

self.W2 = np.random.randn(n_embd, n_embd * 4) # [output_features, input_features]

self.b2 = np.zeros(n_embd)

def forward(self, x):

x = linear(x, self.W1, self.b1)

x = gelu(x)

x = linear(x, self.W2, self.b2)

return x

The feedforward network in the transformer is a simple 2-layered multilayer perceptron or fully connected network. It stacks additional learnable parameters after multi-head attention to facilitate learning.

That was all! Yes, we have finished writing the entire code for the transformer architecture in GPT-2.

Putting Everything Together

Assembling everything in one place, we get the architecture of GPT-2.

As we discussed earlier, we are using tiktoken for the tokenizer. It is also shown at the end of the code how a statement is processed through the GPT-2 architecture.

import numpy as np

import tiktoken

tokenizer = tiktoken.encoding_for_model("gpt-2")

# Helper functions

def linear(input, weight, bias=None):

# Weight matrix should be in the shape of (output_features, input_features)

# Perform matrix multiplication accordingly

output = np.dot(input, weight.T) # No additional transpose needed on the weight matrix

if bias is not None:

output += bias

return output

def gelu(x):

return 0.5 * x * (1 + np.tanh(np.sqrt{2 / np.pi} * (x + 0.044715 * np.power(x, 3))))

def embedding(vocab_size, embedding_dim):

return np.random.randn(vocab_size, embedding_dim)

def softmax(x):

e_x = np.exp(x - np.max(x, axis=-1, keepdims=True))

return e_x / np.sum(e_x, axis=-1, keepdims=True)

def layernorm(x, gamma, beta, epsilon=1e-5):

mean = np.mean(x, axis=-1, keepdims=True)

variance = np.mean(np.square(x - mean), axis=-1, keepdims=True)

normalized_x = (x - mean) / np.sqrt(variance + epsilon)

return gamma * normalized_x + beta

# Parameters setup

n_embd = 768

n_layer = 12

n_head = 12

n_positions = 1024

vocab_size = 50257

class AttentionHead:

def __init__(self, embd_size, head_size):

self.W_q = np.random.randn(head_size, embd_size)

self.W_k = np.random.randn(head_size, embd_size)

self.W_v = np.random.randn(head_size, embd_size)

self.tril = np.tril(np.ones((n_positions, n_positions)))

def forward(self, x):

q = linear(x, self.W_q)

k = linear(x, self.W_k)

v = linear(x, self.W_v)

k_transpose = k.transpose(0, 2, 1) # Transposing for proper matrix multiplication

wei = np.matmul(q, k_transpose) / np.sqrt(k.shape[-1])

wei = np.where(self.tril[:x.shape[1], :x.shape[1]] == 0, -np.inf, wei)

wei = softmax(wei)

out = np.matmul(wei, v)

return out

class MultiHeadAttention:

def __init__(self, embd_size, num_heads):

self.heads = [AttentionHead(embd_size, embd_size // num_heads) for _ in range(num_heads)]

self.proj = np.random.randn(embd_size, embd_size) # Correct projection matrix

def forward(self, x):

head_outputs = [head.forward(x) for head in self.heads]

concat = np.concatenate(head_outputs, axis=2)

return linear(concat, self.proj)

class FeedForward:

def __init__(self, n_embd):

# Adjust dimension order for weight matrices

self.W1 = np.random.randn(n_embd * 4, n_embd) # [output_features, input_features]

self.b1 = np.zeros(n_embd * 4)

self.W2 = np.random.randn(n_embd, n_embd * 4) # [output_features, input_features]

self.b2 = np.zeros(n_embd)

def forward(self, x):

x = linear(x, self.W1, self.b1)

x = gelu(x)

x = linear(x, self.W2, self.b2)

return x

class TransformerBlock:

def __init__(self, n_embd, n_head):

self.attn = MultiHeadAttention(n_embd, n_head)

self.ffn = FeedForward(n_embd)

self.ln1 = np.ones(n_embd), np.zeros(n_embd) # Gamma, Beta for LayerNorm

self.ln2 = np.ones(n_embd), np.zeros(n_embd)

def forward(self, x):

x = x + self.attn.forward(layernorm(x, *self.ln1))

x = x + self.ffn.forward(layernorm(x, *self.ln2))

return x

class GPT2:

def __init__(self):

self.token_emb = embedding(vocab_size, n_embd)

self.pos_emb = embedding(n_positions, n_embd)

self.transformer_blocks = [TransformerBlock(n_embd, n_head) for _ in range(n_layer)]

def forward(self, inputs):

x = self.token_emb[inputs] + self.pos_emb[np.arange(inputs.shape[1]) % n_positions]

for block in self.transformer_blocks:

x = block.forward(x)

x = x @ self.token_emb.T # Projection to vocabulary size

return x

# Create a GPT2 model instance

model = GPT2()

# Processing a sentence

sentence = "Hello There! How are you doing today?"

token_ids = tokenizer.encode(sentence) # Tokenizing the sentence

# Ensure token_ids are within our assumed vocabulary size

token_ids = [tid % vocab_size for tid in token_ids]

# Running through the model

inputs = np.array([token_ids]) # Shape (1, sequence_length)

output = model.forward(inputs)

print(output.shape) # Output shape should be (1, sequence_length, n_embd)

Hurray! We just implemented the architecture of GPT-2 from scratch.

But a few things to note: Implementing the architecture is cool, but it’s missing a ton of further details on how exactly these Language Models work. Here are some aspects that are not covered in this post:

- Backpropagation: Yes, we have only written the forward propagation code for the GPT, but we have not touched on how the pre-training and fine-tuning of these language models happen. This is beyond the scope of this blog post.

- Decoding Strategies: We left the implementation at generating the output embedding from the provided text. However, various strategies are used for generating text in language models, such as greedy search, beam search, top-k sampling, top-p sampling, temperature sampling, etc. Each of these strategies has its own strengths and weaknesses, and the choice of which to use can depend on the specific requirements of the text generation task.

- GPU Support: We have implemented this entire thing in bare Numpy! This code is not compatible to be run on any GPU/TPU.

- Inference Optimization: Our current implementation lacks efficiency. To achieve significant and immediate optimization (aside from GPU and batching support), we should implement a key-value (kv) cache. Additionally, our attention head computations are currently performed sequentially. To enhance performance, we should switch to parallel processing for these computations.

- Evaluation: There is a lot involved in this. Traditionally, LLMs are tested on a bunch of traditional benchmarks. Our implementation is far from the stage of even starting training, let alone benchmarking.

- Fine-Tuning: Language models often need to undergo methods such as RLHF, which requires human involvement to be able to generate expected outputs.